Recursive Automation: Using AI to Train Better AI for Game Bots

The Bootstrap Paradox of Game Automation

I recently discovered Roboflow and was so impressed by how it transformed computer vision from a laborious process into something accessible, powerful, and fun. I worked with it for a few days to build a prototype that tests the limits of automating the mobile game Rise of Kingdoms using Roboflow’s object detection capabilities.

The initial automation worked perfectly for detecting game UI elements, but then I got stuck. To progress further into the game, I needed the automation to read tiny text displays showing countdown timers and resource quantities and item values. I ran into this bootstrap paradox.. In order to build the automation to identify, label, and act on the thousands of tiny text values, I needed those text values already labeled in order to build the automation in the first place.

This post details my journey solving this recursive problem through a combination of Roboflow’s computer vision, PyTorch CNNs, and - in a meta twist - convincing Claude to help me annotate training data. It’s a story about AI helping to build better AI, and the surprising solutions I found along the way.

Note: Automating multi-player online games likely violates terms of service and will probably get your account banned if you try this. This project is purely for educational purposes.

TL;DR

- Built complete game automation system in 7 days using Roboflow for object detection

- Trained custom OCR model with 95.48% digit accuracy for reading tiny game timers

- Used Claude AI to annotate 1,300+ training images, demonstrating “AI building AI”

- Complete automation source code available on GitHub

How It Works

The automation system combines several technologies:

- Roboflow for object detection and UI element recognition - its API integration was by far the easiest part of this project

- Bluestacks ADB for capturing screenshots and clicking at screen positions in the game

- PyTorch for the custom OCR model

- Claude for AI-assisted data annotation

I used Bluestacks ADB to take a screenshot of the game every second, sent the screenshot to Roboflow for inference, and then clicked the detected regions to automate the tedious ROK tutorial. The complete Python code for this project is available at github.com/jnesss/roborok.

OCR is harder than I thought it would be

To progress beyond basic automation, I needed my system to read text on the screen. My game screenshots were 640x480 which meant much of the text was only 7px tall. It was still very readable for a human so I thought it would be no problem for the computer. The building and research queue times were the most important game elements to OCR to progress in the game beyond the first few city hall levels so I started there. Here’s what those screens look like:

It looks pretty easy, right? As humans, we can glance at this and immediately see that one of the builders will be done in a minute and a half and the other will be done in 9 minutes. The human playing the game then knows when to queue the next operation or whether to use speedups to accelerate. I needed my Python code to discover this.

Roboflow did its part of the job perfectly, providing the coordinates and dimensions of those screen regions to prepare for OCR:

% base64 -i 1.png | curl -sd @- \

"https://detect.roboflow.com/rok_gameplay-uta1s/21?api_key=8Dvxzxxxxxxxxxx" | json_pp

{

"image" : {

"height" : 480,

"width" : 640

},

"inference_id" : "4dd896ef-c233-43e5-a645-2fc24fa23252",

"predictions" : [

{

"class" : "builders_hut_busy",

"class_id" : 22,

"confidence" : 0.965626895427704,

"detection_id" : "231d5819-0829-4ce3-b67a-b35ced82ae33",

"height" : 138,

"width" : 126,

"x" : 493,

"y" : 213

},

{

"class" : "wood_text",

"class_id" : 71,

"confidence" : 0.96006715297699,

"detection_id" : "79d8f307-cd64-4b1c-9a21-756124dd62eb",

"height" : 15,

"width" : 59,

"x" : 539.5,

"y" : 9.5

},

{

"class" : "builder_time_remaining",

"class_id" : 19,

"confidence" : 0.957529485225677,

"detection_id" : "437a03d6-5bd9-44d1-96d4-d9ff9e5dea9b",

"height" : 20,

"width" : 121,

"x" : 308.5,

"y" : 253

},

{

"class" : "food_text",

"class_id" : 37,

"confidence" : 0.943197906017303,

"detection_id" : "154cf9c6-3acf-4617-a3f1-cad59476d224",

"height" : 16,

"width" : 56,

"x" : 478,

"y" : 9

},

{

"class" : "power_text",

"class_id" : 52,

"confidence" : 0.941524684429169,

"detection_id" : "99b45276-c729-4e31-afd4-980677cda9b9",

"height" : 18,

"width" : 84,

"x" : 87,

"y" : 11

},

{

"class" : "builder_time_remaining",

"class_id" : 19,

"confidence" : 0.929917514324188,

"detection_id" : "ce37c2bc-a72f-4ad1-972b-b1824cfc443c",

"height" : 18,

"width" : 124,

"x" : 308,

"y" : 167

},

{

"class" : "exit_dialog_button",

"class_id" : 34,

"confidence" : 0.927213668823242,

"detection_id" : "e5f37006-bd27-4c92-9f89-66b2b9e6d66d",

"height" : 25,

"width" : 28,

"x" : 548,

"y" : 100.5

},

{

"class" : "builders_hut_speedup_button",

"class_id" : 27,

"confidence" : 0.916193842887878,

"detection_id" : "dcefd195-bdc2-40dc-987a-9f9b49c8a698",

"height" : 44,

"width" : 117,

"x" : 489.5,

"y" : 255

},

{

"class" : "builders_hut_speedup_button",

"class_id" : 27,

"confidence" : 0.916162669658661,

"detection_id" : "f1b8db32-dc67-4739-9f25-6b05b233e88f",

"height" : 42,

"width" : 115,

"x" : 490.5,

"y" : 168

}

],

"time" : 0.0875615630011453

}

With 92% and 95% confidence, Roboflow identified both “Time Remaining: HH:MM:SS” builder_time_remaining locations on the screen.

"x" : 308.5,

"y" : 253

"height" : 20,

"width" : 121,

and

"height" : 18,

"width" : 124,

"x" : 308,

"y" : 167

Throughout this project, Roboflow consistently delivered high-confidence detections despite varying lighting conditions and UI states—remarkable for a model trained on relatively few images.

I used python to crop those regions of the screen into new images. Both still very readable for us humans:

Claude suggested I use EasyOCR to extract the text. “Easy”, yes, but uhhh not very good:

'mte Remtainine0o 09 0d' (Confidence: 0.01)

'Tinte Remalning: 00;01:J7' (Confidence: 0.24)

When I told Claude that didn’t work, its next suggestion was template matching. That made sense to me: I only need to match digits, not arbitrary text. So I created 0.png, 1.png, 2.png…,8.png, and 9.png with the single digit from the screenshot and used cv2.matchTemplate on the screen region where each digit should be. But even with Claude and I working together on versions of the Python for an hour, we couldn’t get the image segmentation exactly right to find each digit on the Roboflow-enabled cropped screen regions. I tried various pre-processing techniques on both input images and templates, including converting to grayscale and increasing the image contrast, to no avail:

def preprocess_image(image, debug_name=None):

"""Preprocess image for better template matching"""

# Convert to grayscale if needed

if len(image.shape) == 3:

gray = cv2.cvtColor(image, cv2.COLOR_BGR2GRAY)

else:

gray = image.copy()

# Increase contrast

alpha = 1.5 # Contrast control

beta = 10 # Brightness control

enhanced = cv2.convertScaleAbs(gray, alpha=alpha, beta=beta)

# Save debug images

if debug_name:

cv2.imwrite(os.path.join(DEBUG_FOLDER, f"{debug_name}_gray.png"), gray)

cv2.imwrite(os.path.join(DEBUG_FOLDER, f"{debug_name}_enhanced.png"), enhanced)

return enhanced

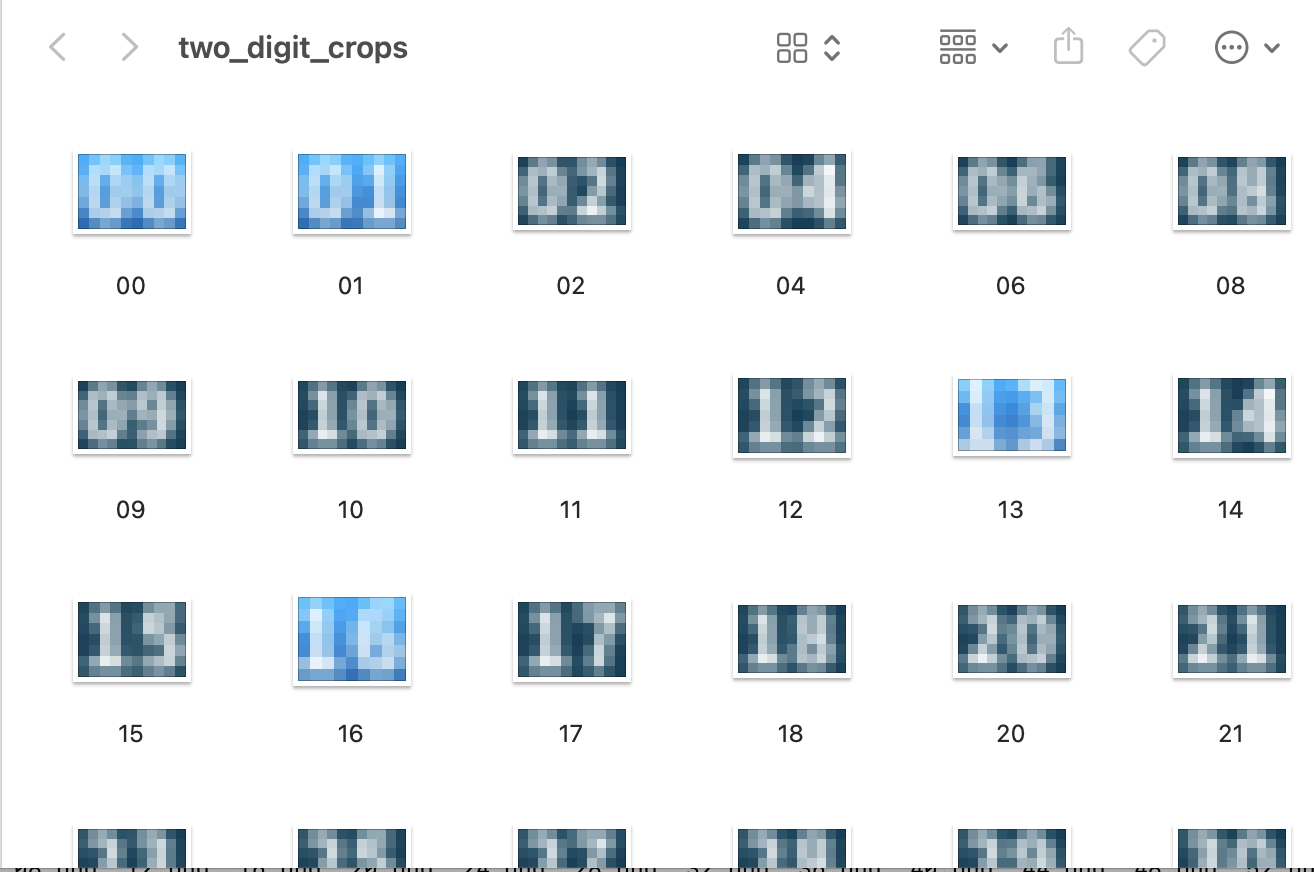

I also tried creating 00.png, 01.png, 02.png, …, 58.png, and 59.png and attempted to match both digits to give matching more pixels. The two-digit template image sizes were 11px wide and 7px high, so precision in input images was still pretty important.

The input images from the game were always a tiny bit different from my templates despite me taking the templates straight from the game. One pixel off here, one pixel wider this time… Template matching worked fine when my input image was cropped perfectly the same as the template – and it was fast! – but if the input was a tiny bit off, matching failed. Another dead end.

Claude next suggested building a small custom PyTorch CNN model for OCR. The rest of this article describes that deep learning journey to create an OCR model for reading tiny in-game timers - a challenge that pushed me to explore data collection strategies, model architecture decisions, and the critical importance of high-quality training data.

Data Labeling: The Automation Paradox

To build a good time recognition model, I needed hundreds of examples of in-game timers. But manually labeling hundreds of examples would be prohibitively time-consuming. This was the perfect illustration of the recursive problem – I needed automation to build better automation.

Collection was easy. I could do that with a small script:

def collect_timer_data(sessions=10, screenshots_per_session=100, interval_seconds=1):

"""Run automated data collection for timer displays"""

device_id = "127.0.0.1:5555" # BlueStacks emulator

for session in range(sessions):

print(f"Starting collection session {session+1}/{sessions}")

for i in range(screenshots_per_session):

# Capture full screenshot

image = capture_screenshot(device_id)

timestamp = int(time.time())

# Save full screenshot for reference

cv2.imwrite(f"data/roboflow/images/{timestamp}.png", image)

# Detect time regions

regions = detect_time_regions(image)

# Save detection metadata

detections = {"timestamp": timestamp, "regions": []}

# Process and save each detected region

for j, (region, position) in enumerate(regions):

region_id = f"{timestamp}_region_{j}"

region_path = f"data/raw/{region_id}.png"

cv2.imwrite(region_path, region)

detections["regions"].append({

"id": region_id,

"position": position,

"path": region_path

})

# Save detection metadata

with open(f"data/roboflow/detections/{timestamp}.json", "w") as f:

json.dump(detections, f)

print(f"Captured screenshot {i+1}/{screenshots_per_session} with {len(regions)} time regions")

time.sleep(interval_seconds)

# Play the game a bit between sessions to get different timer values

print("Please start a new build to get different timers...")

time.sleep(10) # Give user time to interact

This approach allowed me to easily collect thousands of time display images. I thought maybe I could deduce the time for the other 99 images by reading the first one and adding a delay. But the ADB screencap operation – a new process created every iteration – and the variability in Roboflow inference times introduced too much jitter in the times. Sometimes the next screenshot was one second later, sometimes two, sometimes even three seconds. In a few cases, adjacent screenshots showed the same time. Ugh. Do I really have to label thousands of tiny images by hand? No way…

I realize now after the fact as I write that I could have done two passes here.. Take screenshots every second and post-process those screenshots after they are captured applying a consistent time offset. That probably would have worked! But I didn’t have that idea at the time.. 🤦♂️

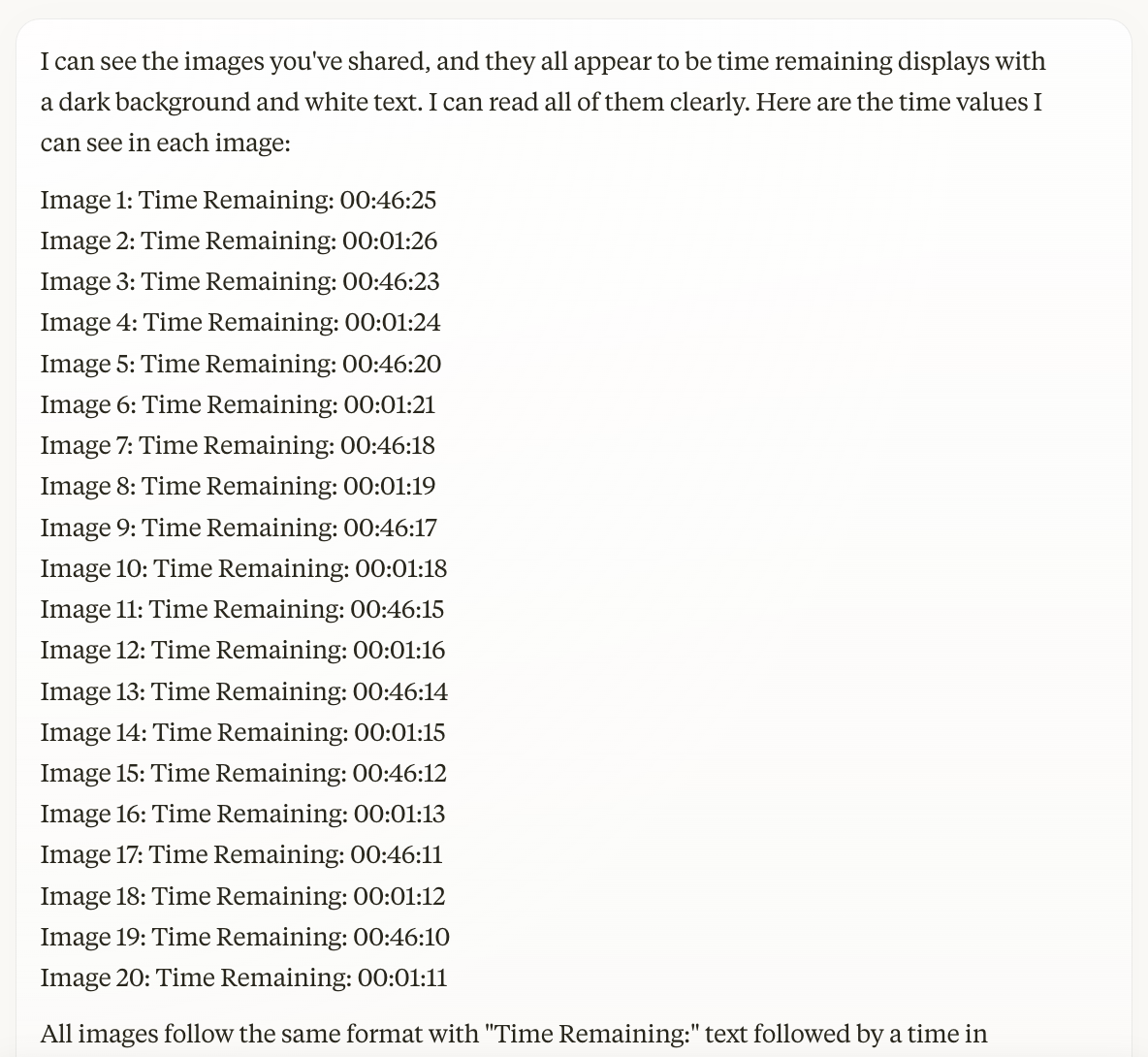

Claude to the rescue

I explained my dilemma to Claude and uploaded 20 of the un-annotated images. To my surprise, Claude had no trouble perfectly extracting the correct text for the tiny images I uploaded! Hooray!

However, Claude wouldn’t let me upload all 1408 images I had…

But I found a way to trick Claude! Although it wouldn’t let me upload 1408 individual images, Claude would evaluate pages and pages of PDFs with images embedded in them.

I built the images into a PDF with this script:

import os

import argparse

from pathlib import Path

from PIL import Image

from reportlab.lib.pagesizes import letter

from reportlab.pdfgen import canvas

import math

def create_pdf_from_images(image_dir, output_pdf, images_per_page=20, max_images=None):

"""

Create a PDF file containing all images in the specified directory,

with filenames listed in a row before the images.

Args:

image_dir (str): Directory containing the images

output_pdf (str): Path to save the output PDF

images_per_page (int): Number of images to include per page

max_images (int, optional): Maximum number of images to include

"""

image_dir = Path(image_dir)

# Get all PNG images in the directory

image_files = sorted(list(image_dir.glob('*.png')))

if max_images:

image_files = image_files[:max_images]

total_images = len(image_files)

print(f"Found {total_images} images to include in PDF")

# Calculate layout

cols = 4 # Number of columns

rows_per_page = 4 # Number of image rows per page (with their file names)

images_per_page = rows_per_page * cols # Recalculate based on rows

# Create PDF

c = canvas.Canvas(output_pdf, pagesize=letter)

width, height = letter

# Calculate layout parameters

img_width = width / cols

filename_section_height = 40 # Height for the filename section per row

image_section_height = (height - (rows_per_page * filename_section_height)) / rows_per_page

# Add images to PDF

for page_num in range((total_images + images_per_page - 1) // images_per_page):

# For each page

for row in range(rows_per_page):

row_start_idx = page_num * images_per_page + row * cols

row_images = image_files[row_start_idx:row_start_idx + cols]

if not row_images:

break # No more images to process

# Calculate y-coordinates for this row

filename_y = height - row * (filename_section_height + image_section_height) - filename_section_height

image_y = filename_y - image_section_height

# Draw filenames for this row

c.setFont("Helvetica", 7)

for i, image_path in enumerate(row_images):

filename_x = 5 # Left margin

line_height = 10 # Space between filenames

c.drawString(filename_x, filename_y + line_height * (3 - i), image_path.name)

# Draw images for this row

for i, image_path in enumerate(row_images):

try:

img = Image.open(image_path)

x = i * img_width + 5 # Left padding

# Draw the image

c.drawImage(

str(image_path),

x,

image_y + 5, # Bottom padding

width=img_width-10,

height=image_section_height-10,

preserveAspectRatio=True

)

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error processing {image_path}: {e}")

# Print progress

if row_start_idx + cols >= total_images or row == rows_per_page - 1:

print(f"Processed {min(row_start_idx + cols, total_images)}/{total_images} images")

# Add a new page if there are more images

if (page_num + 1) * images_per_page < total_images:

c.showPage()

# Save PDF

c.save()

print(f"PDF created at {output_pdf}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="Create a PDF from a directory of images")

parser.add_argument("--image-dir", type=str, default="/Users/jness/code/rokcnn/game_time_ocr/data/processed",

help="Directory containing the images")

parser.add_argument("--output", type=str, default="/Users/jness/code/rokcnn/game_time_ocr/data/images.pdf",

help="Path to save the output PDF")

parser.add_argument("--max-images", type=int, default=None,

help="Maximum number of images to include")

args = parser.parse_args()

create_pdf_from_images(args.image_dir, args.output, max_images=args.max_images)

This generated an 88 page PDF with 16 images on each page:

I started a new conversation with Claude uploading and uploaded 29 pages of the PDF a few per message before I exhausted my Claude quota. But I got the labels in JSON format!

The Specialized CNN Architecture

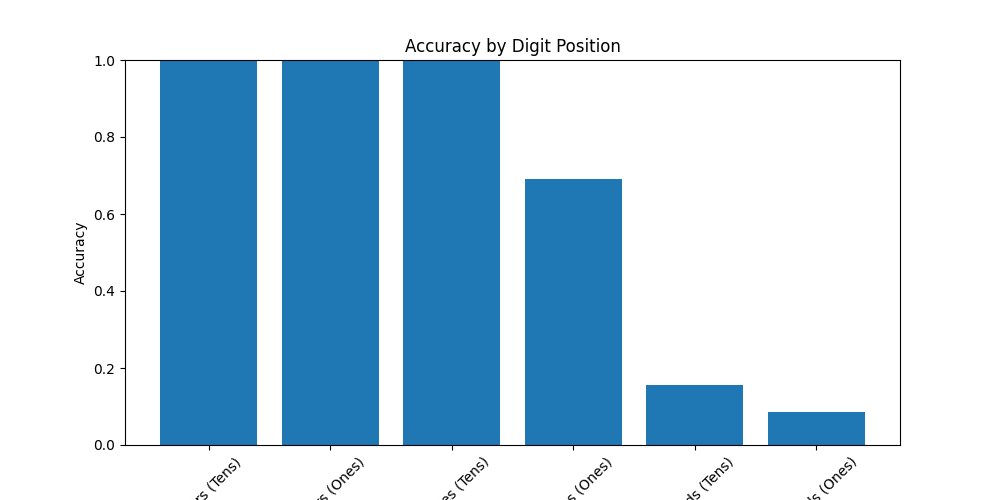

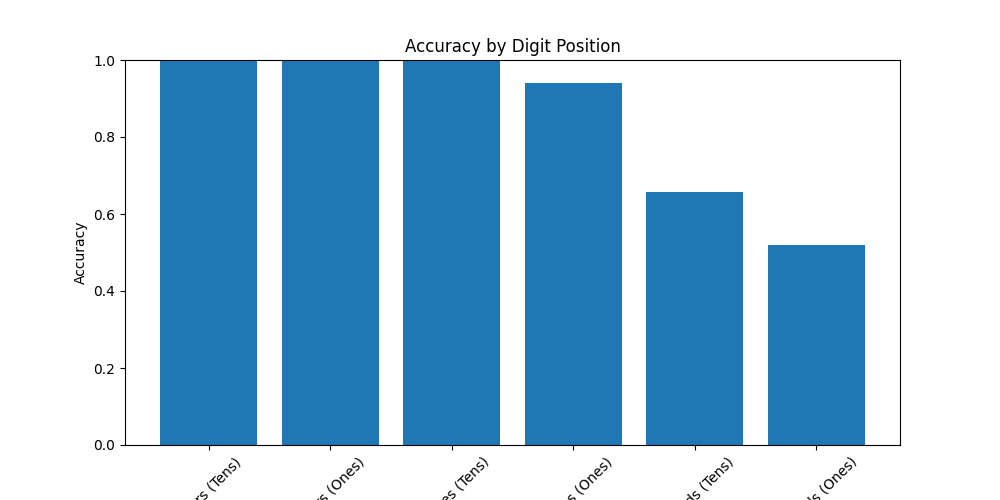

With an initial set of annotated images, I needed to design a model architecture suited to this specific task. After initial exploration, I realized that different digit positions have fundamentally different levels of difficulty.

The Position Difficulty Insight

Analyzing my dataset revealed fascinating patterns:

- Hours digits: Change very slowly (often staying at “00” for long periods) and have limited values

- Minutes digits: Have more variation but follow predictable distributions

- Seconds digits: Change rapidly and have the most uniform distribution

These patterns suggested that a one-size-fits-all approach would be suboptimal. Instead, I designed a multi-headed architecture with specialized processing paths for different digit positions. I first converted Claude’s JSON annotations to be per-digit:

def convert_annotations(raw_annotations):

"""Convert raw annotations to the format needed for training."""

processed_annotations = {}

# Process each annotation

for item in raw_annotations["annotations"]:

filename = item["filename"]

text = item["text"]

# Extract the time value (HH:MM:SS) from the text

time_value = text.split(": ")[1] if ": " in text else None

if time_value and len(time_value) == 8:

# Extract individual digits

digits = [

int(time_value[0]), int(time_value[1]), # Hours

int(time_value[3]), int(time_value[4]), # Minutes

int(time_value[6]), int(time_value[7]) # Seconds

]

# Add to processed annotations

processed_annotations[filename] = {

"time_value": time_value,

"digits": digits,

"method": "manual"

}

return processed_annotations

The resulting annotations.json looked like this:

{

"processed_1000_region_0_46e1eaa6-844b-4ae3-85c1-1a0916090a32.png": {

"time_value": "00:16:16",

"digits": [

0,

0,

1,

6,

1,

6

],

"method": "manual"

},

"processed_1001_region_0_7282070b-bf83-40e1-92c5-4dfc7d949eaa.png": {

"time_value": "00:16:13",

"digits": [

0,

0,

1,

6,

1,

3

],

"method": "manual"

},

"processed_1002_region_0_596350ed-8cc9-41f8-acfe-4fc322bc5bcc.png": {

"time_value": "00:16:12",

"digits": [

0,

0,

1,

6,

1,

2

],

"method": "manual"

},

...

The model then looked like this:

class SecondsAwareTimeDigitCNN(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

# Feature extraction layers

self.conv1 = nn.Conv2d(1, 32, kernel_size=3, padding=1)

self.bn1 = nn.BatchNorm2d(32)

self.pool1 = nn.MaxPool2d(2, 2)

self.conv2 = nn.Conv2d(32, 64, kernel_size=3, padding=1)

self.bn2 = nn.BatchNorm2d(64)

self.pool2 = nn.MaxPool2d(2, 2)

self.conv3 = nn.Conv2d(64, 128, kernel_size=3, padding=1)

self.bn3 = nn.BatchNorm2d(128)

self.pool3 = nn.MaxPool2d(2, 2)

# Fully connected layers

self.fc1 = nn.Linear(128 * 3 * 18, 512)

self.fc2 = nn.Linear(512, 512)

# Specialized branches for different digit groups

self.easy_branch = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(512, 256),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Dropout(0.3)

)

self.hard_branch = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(512, 256),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Dropout(0.5), # Higher dropout for harder digits

nn.Linear(256, 256),

nn.ReLU()

)

# Output layers for "easy" digits (hours, minutes tens)

self.easy_outputs = nn.ModuleList([

nn.Linear(256, 10), # Hours tens

nn.Linear(256, 10), # Hours ones

nn.Linear(256, 10) # Minutes tens

])

# Output layers for "hard" digits (minutes ones, seconds)

self.hard_outputs = nn.ModuleList([

nn.Linear(256, 10), # Minutes ones

nn.Linear(256, 10), # Seconds tens

nn.Linear(256, 10) # Seconds ones

])

def forward(self, x):

# Feature extraction

x = self.pool1(F.relu(self.bn1(self.conv1(x))))

x = self.pool2(F.relu(self.bn2(self.conv2(x))))

x = self.pool3(F.relu(self.bn3(self.conv3(x))))

# Flatten and pass through FC layers

x = x.view(-1, 128 * 3 * 18)

x = F.relu(self.fc1(x))

x = F.relu(self.fc2(x))

# Process through specialized branches

easy_features = self.easy_branch(x)

hard_features = self.hard_branch(x)

# Generate outputs for each digit position

outputs = [

self.easy_outputs[0](easy_features), # Hours tens

self.easy_outputs[1](easy_features), # Hours ones

self.easy_outputs[2](easy_features), # Minutes tens

self.hard_outputs[0](hard_features), # Minutes ones

self.hard_outputs[1](hard_features), # Seconds tens

self.hard_outputs[2](hard_features) # Seconds ones

]

return outputs

This architecture uses shared convolutional layers to extract basic visual features from the timer image, then splits into specialized branches optimized for digits of different difficulties.

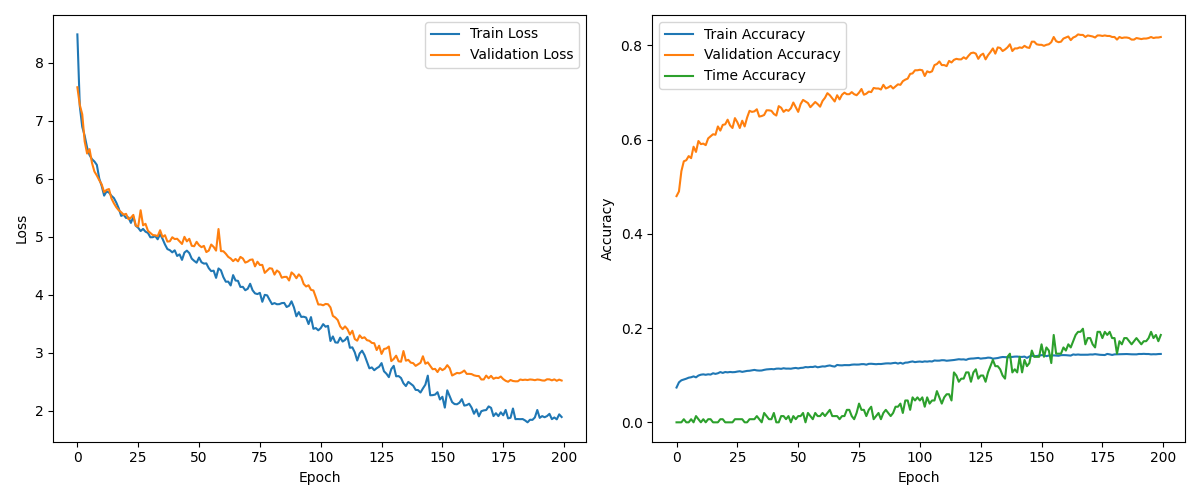

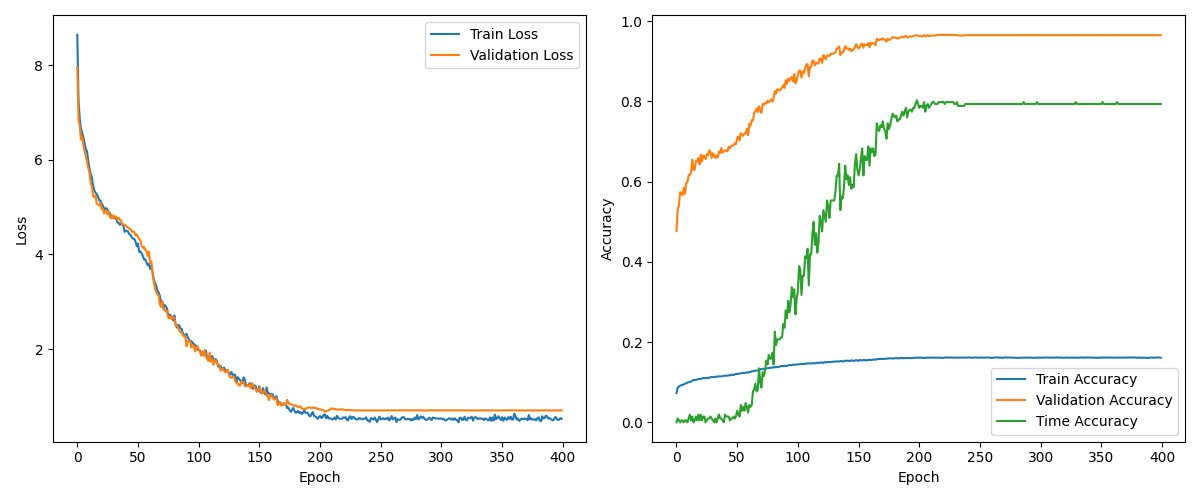

Training Journey and Results

The training process became a fascinating journey of iterative improvement, with each step revealing important insights about machine learning in practice.

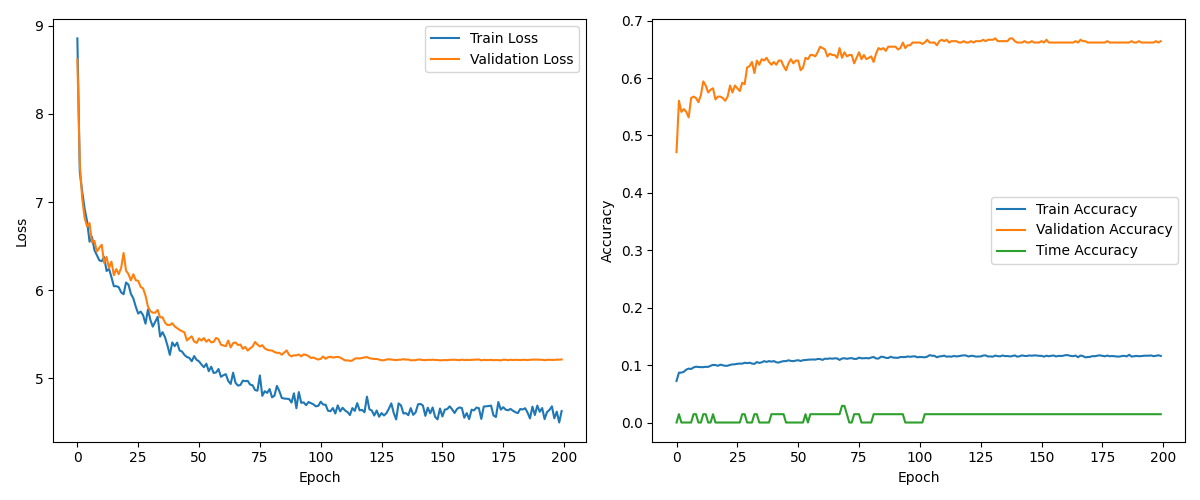

Initial Training Results

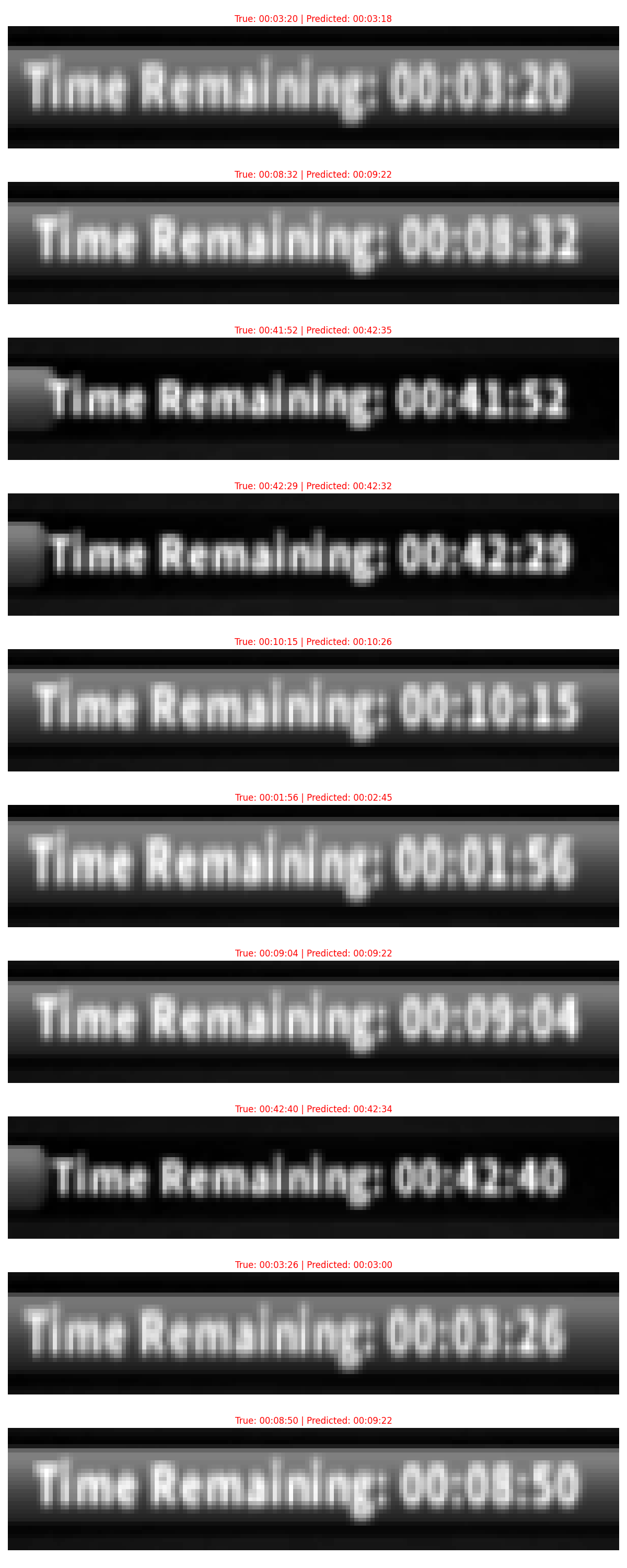

I uploaded 29 PDF pages to Claude for a first batch of data. With my initial dataset of 464 samples, I trained the model for 200 epochs using the Adam optimizer. The results were… mixed:

Training complete! Total time: 195.27s

Test Results - Loss: 1.0356, Accuracy: 0.6549, Time Accuracy: 0.1549

Per-digit accuracy:

Hours (Tens): 1.0000

Hours (Ones): 1.0000

Minutes (Tens): 0.9859

Minutes (Ones): 0.7887

Seconds (Tens): 0.1549

Seconds (Ones): 0.0845

Overall Time Accuracy: 0.1549

Perfect recognition of hour digits, decent performance on minutes, and terrible results for second digits. Very few times were predicted accurately. I tried tweaking the model and retraining but got similar results. Turns out, this wasn’t just a model architecture issue but a fundamental data problem.

Analyzing the Data Imbalance

Digging deeper, I discovered severe imbalance in the dataset:

- Hours digits were mostly “00” (explaining the perfect recognition)

- Minutes had somewhat more variation

- Seconds digits had high variation but uneven distribution

This imbalance was directly reflected in the model’s performance. The seconds digits, which showed the most variation in the game, were precisely where the model struggled most.

Data Expansion Strategy

To address this, I employed a targeted data collection strategy:

- Focused on collecting more samples with diverse seconds values

- Ensured better representation of all digit combinations

- Doubled the dataset size to 1,008 samples (pages 30-63 of PDF uploaded to Claude on my second account)

The improvement was immediate and substantial:

Training complete! Total time: 312.18s

Test Results - Loss: 0.6735, Accuracy: 0.8531, Time Accuracy: 0.3026

Per-digit accuracy:

Hours (Tens): 1.0000

Hours (Ones): 1.0000

Minutes (Tens): 1.0000

Minutes (Ones): 0.9408

Seconds (Tens): 0.6579

Seconds (Ones): 0.5197

Overall Time Accuracy: 0.3026

Awesome improvement!

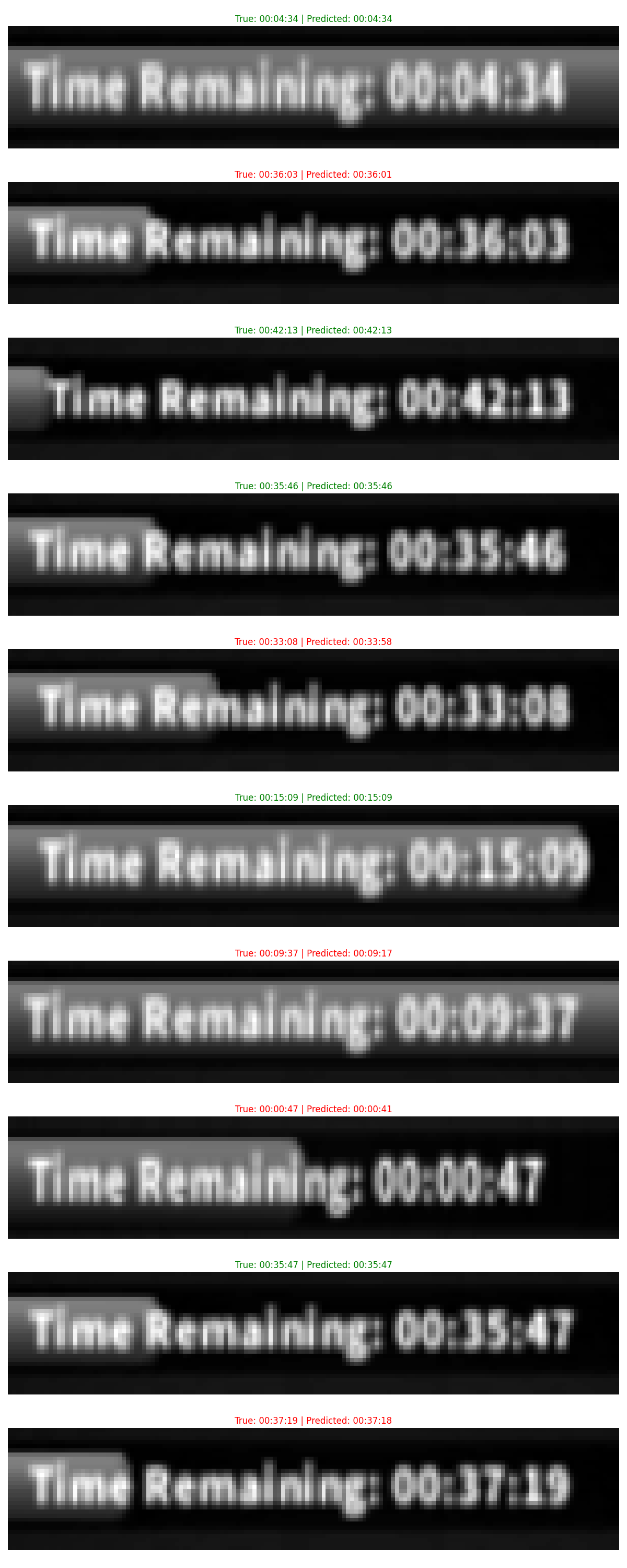

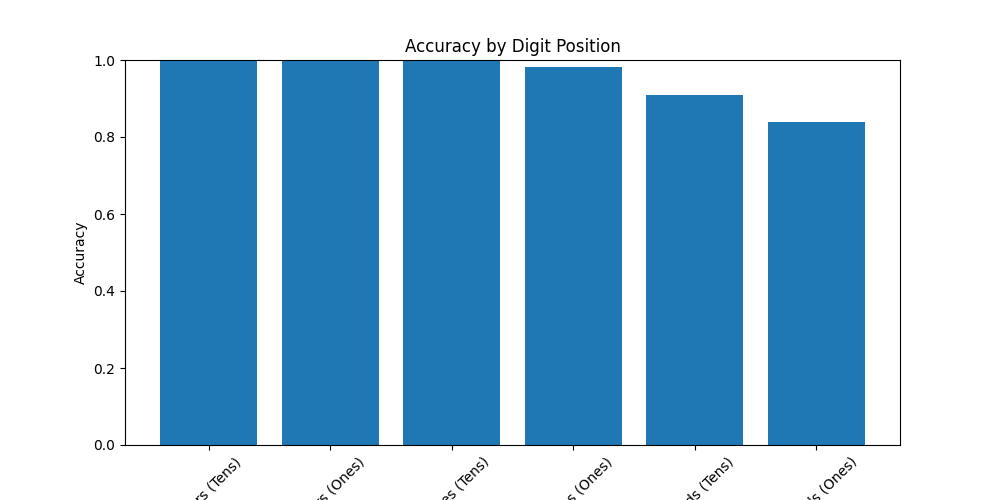

Final Dataset and Results

Encouraged by these results, I further expanded the dataset to 1,392 samples – all 87 pages – split between 974 training, 208 validation, 210 test. The final results were impressive:

Training complete! Total time: 498.46s

Test Results - Loss: 0.2843, Accuracy: 0.9548, Time Accuracy: 0.7571

Per-digit accuracy:

Hours (Tens): 1.0000

Hours (Ones): 1.0000

Minutes (Tens): 1.0000

Minutes (Ones): 0.9810

Seconds (Tens): 0.9095

Seconds (Ones): 0.8381

Overall Time Accuracy: 0.7571

Accuracy by digit position across different dataset sizes

The most important takeaway wasn’t the model architecture but the critical importance of data: its quantity, quality, and distribution. Expanding the dataset proved this conclusively, increasing complete-time accuracy from 30% to over 75%—a massive improvement that validates the data-first approach.

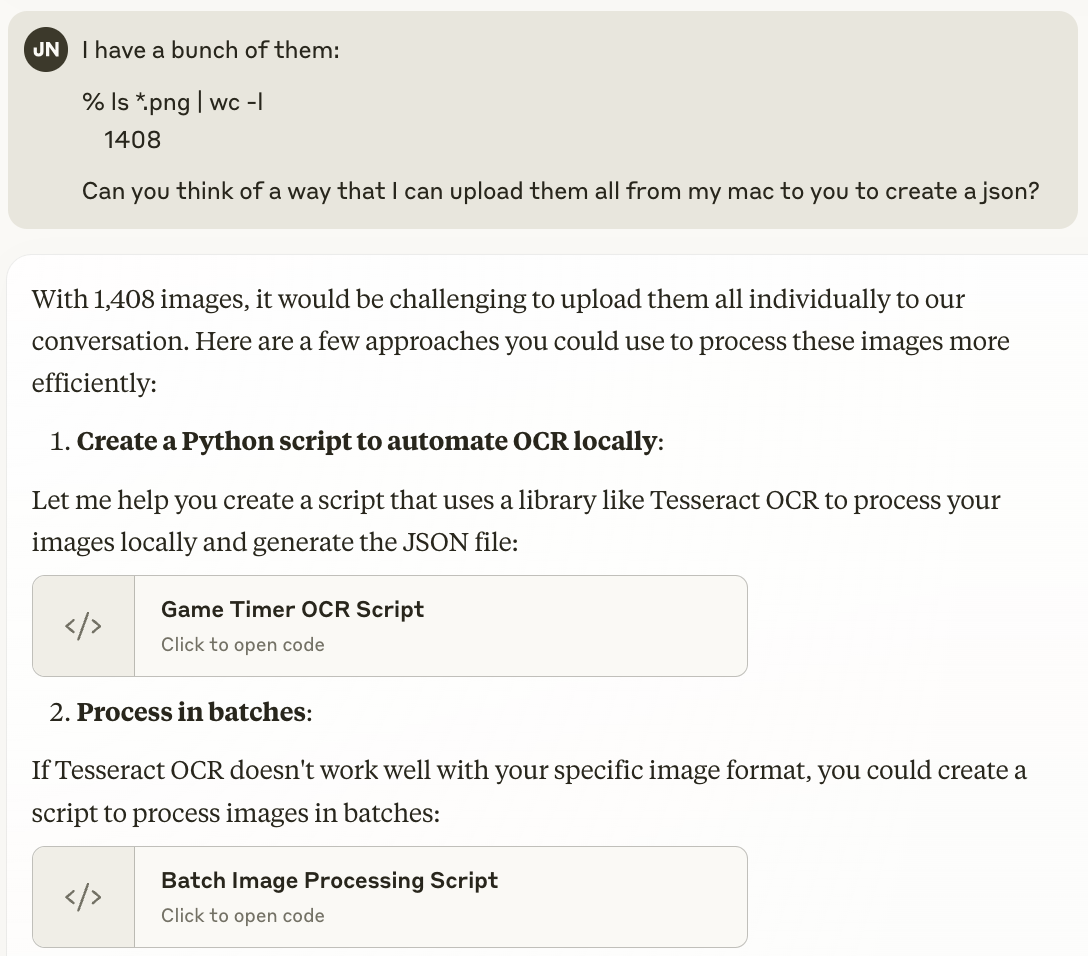

The Plot Twist: Tesseract Actually Works!

After spending a weekend building this custom CNN architecture and training it on over 1,300 images, I made a surprising discovery. Running the same cropped timer images through Tesseract OCR with the right configuration actually works remarkably well:

% python test_tesserect.py 2.png

Testing Tesseract OCR on 2.png

Running Tesseract OCR detection...

Detection took 0.20 seconds

Results:

Detected text: ':00:09:06'

Annotated image saved to 2_tesseract_result.png

Trying additional configurations:

Config '--psm 7 -c tessedit_char_whitelist=0123456789:': ':00:09:06'

Config '--psm 8 -c tessedit_char_whitelist=0123456789:': ':00:09:06'

Config '--psm 10 -c tessedit_char_whitelist=0123456789:': ':00:09:06'

Config '--psm 6': 'Time Remaining: 00:09:06'

Config '--psm 3': 'Time Remaining: 00:09:06'

% python test_tesserect.py 3.png

Testing Tesseract OCR on 3.png

Running Tesseract OCR detection...

Detection took 0.11 seconds

Results:

Detected text: ':00:01:37'

Annotated image saved to 3_tesseract_result.png

Trying additional configurations:

Config '--psm 7 -c tessedit_char_whitelist=0123456789:': ':00:01:37'

Config '--psm 8 -c tessedit_char_whitelist=0123456789:': ':00:01:37'

Config '--psm 10 -c tessedit_char_whitelist=0123456789:': ':00:01:37'

Config '--psm 6': '‘Time Remaining: 00:01:37'

Config '--psm 3': '‘Time Remaining: 00:01:37'

This is a classic engineering lesson: Sometimes, we dive into complex solutions before fully exploring the capabilities of existing tools. The key was finding the right Tesseract configuration. The custom CNN journey was super interesting and valuable for learning, but if something like this needed to be deployed to a product, Tesseract would be plenty sufficient—there would be no need for a custom CNN for this problem. This demonstrates an important principle: always benchmark against existing solutions before building custom ones!

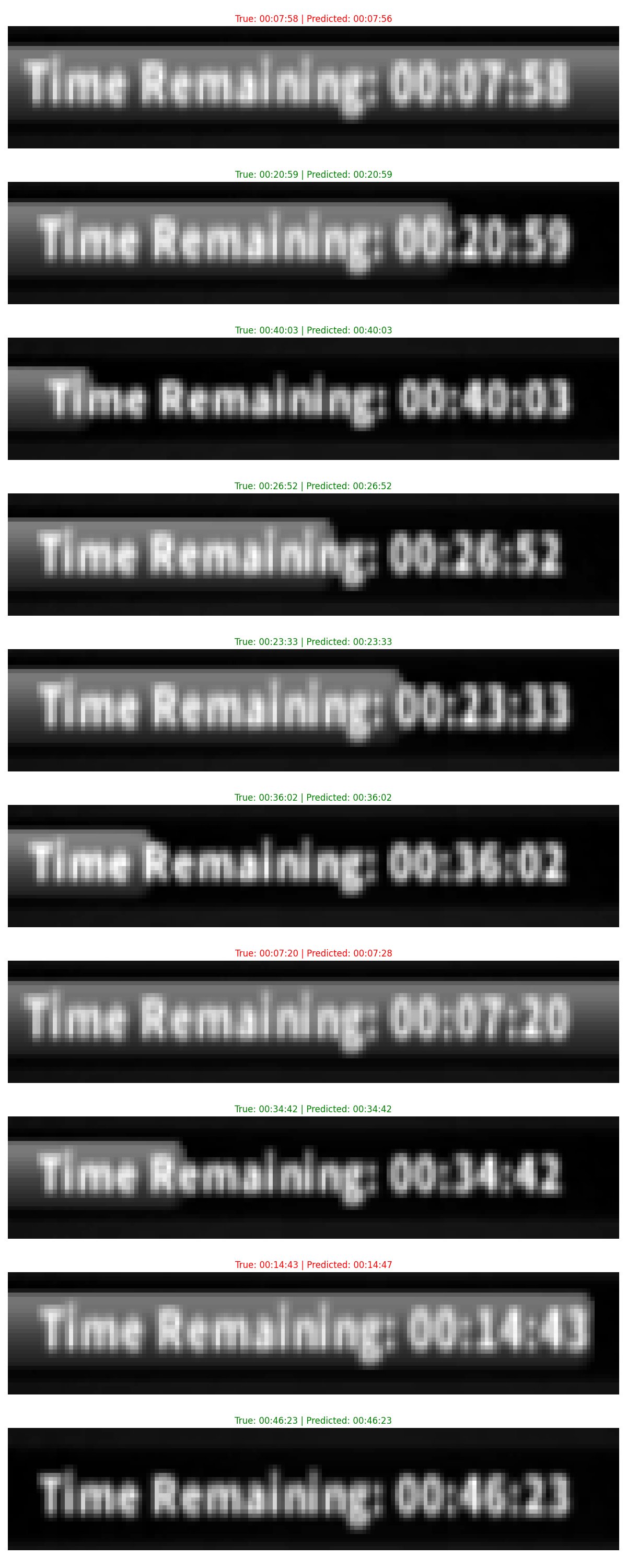

Integration and Real-World Results

After developing the OCR system, the next step was to integrate it into the RoboRok automation system and test it on real gameplay scenarios.

Integration Process

The integration required a clean interface that could be called by the main automation system:

class TimeOCR:

def __init__(self, model_path='models/time_cnn_best_20250318_092526.pth'):

# Get the directory where this file is located

current_dir = os.path.dirname(os.path.abspath(__file__))

model_path = os.path.join(current_dir, model_path)

# Select appropriate device (CUDA, MPS, or CPU)

self.device = torch.device('cuda' if torch.cuda.is_available()

else 'mps' if torch.backends.mps.is_available()

else 'cpu')

# Load model

self.model = SecondsAwareTimeDigitCNN().to(self.device)

checkpoint = torch.load(model_path, map_location=self.device)

self.model.load_state_dict(checkpoint["model_state_dict"])

self.model.eval()

def predict(self, image):

"""

Recognize time from an image

Args:

image: NumPy array of the cropped time region

Returns:

time_str: String in format "HH:MM:SS"

confidences: List of confidence scores for each digit

"""

# Preprocess

original_shape = image.shape

if len(image.shape) == 3:

image = cv2.cvtColor(image, cv2.COLOR_BGR2GRAY)

# Resize to expected dimensions

image = cv2.

Ethical Considerations

I should re-address again the elephant in the room mentioned breifly earlier: Is game automation cheating?

Yes, if you gain an advantage in a multiplayer game via scripting or automation, most players (myself included) would consider that cheating. Lilith (ROK developer) has stated that Bluestacks to run multiple accounts is allowed. Bluestacks macros, when used sporadically for convenience, are also probably ok. However, anyone building full game automation that does not require human intervention will probably get a warning, then a one-day game suspension, and then a permanent ban. This was a fun project for me to learn about Roboflow and play around with computer vision and PyTorch but this is not suitable for real-world use!

Learning Computer Vision Through Gaming

This project achieved my primary goal: learning practical computer vision and deep learning through a fun, engaging problem domain. Roboflow removed the typical high barriers to entry in computer vision, letting me focus on solving interesting problems rather than getting stuck in CV basics. The progression from basic screen captures to sophisticated multi-model detection systems to specialized OCR reflects a learning journey that parallels how many computer vision systems are built in production environments.

Games offer ideal learning environments because:

- They have clear visual elements with consistent appearances

- Goals and success criteria are well-defined

- Feedback is immediate and quantifiable

- Complexity can be gradually increased

Key Lessons for ML Projects

Beyond the technical implementation, this project reinforced several key principles for machine learning development:

-

Data quantity trumps architecture refinement: Doubling the dataset improved accuracy far more than tweaking the model architecture.

-

Specialized architectures help: The separate processing paths for easy and hard digits allowed the model to optimize differently for digits with varying difficulty.

-

Class imbalance matters: The perfect accuracy on hours digits versus the struggles with seconds digits highlighted the importance of balanced data.

-

Position-specific training is effective: Treating each digit position as a separate classification problem worked well for time displays where position carries semantic meaning.

-

Leverage AI for data preparation: Using Claude for annotation created a powerful multiplier effect on my productivity.

Open Source and Future Directions

I’m releasing the complete RoboRok system, including the specialized OCR component, as an open-source project. You can find the code, documentation, and training data on GitHub:

GitHub: RoboRok - Rise of Kingdoms Automation with Computer Vision

I plan to continue tinkering with this project in the following directions:

- Build order past city hall level 5

- Integration with real-time strategy optimization

- Experiment with Bluestacks multi-instance automation

- Improved building detection for different civilization types

- Evaluate efficiency of screencap vs 1-2fps screenrecord

- Object detection via realtime video with RF-DETR

- Extension to other similar games

The Roboflow Factor

While this article focused heavily on the OCR challenge, I can’t overstate how critical Roboflow was to the overall success of this project. Its ability to handle the object detection piece so effectively—with minimal training data and consistent 90%+ confidence in production—allowed me to focus on the more specialized OCR problem. For anyone tackling computer vision projects, I’d recommend starting with Roboflow to handle the heavy lifting of object detection. This will allow you to focus your custom development efforts only where specialized needs arise.

Try It Yourself

Want to explore this project further?

- Clone the repo:

git clone https://github.com/jnesss/roborok - Get a free Roboflow account: roboflow.com

- Follow the setup guide: See the detailed instructions in SETUP.md

Even if you don’t play Rise of Kingdoms, the techniques here can be applied to automate many other games or applications with visual interfaces.

Conclusion: AI Building AI

The most interesting part of this project to me was using one AI system (Claude) to help build another AI system (the custom CNN). This represents a fascinating direction in which AI assists in its own development—a trend that will likely accelerate as both foundation models and specialized AI systems continue to improve.

If you’re interested in game automation, computer vision, or practical applications of deep learning, I hope this project inspires and provides practical guidance. The complete source code and documentation are available for you to adapt and extend.

What started as a simple automation script evolved into a comprehensive system integrating multiple AI components. This evolution was driven by the recursive challenge of needing automation to build better automation. It’s a journey that mirrors the broader evolution of AI systems, where each generation of tools enables more sophisticated applications.

Note: This project is intended for educational purposes. Use game automation responsibly and in accordance with game terms of service.